Table of Contents

Lovecraft Country, HBO’s new horror series built on pulp fiction and Jim Crow Americana, teems with creepy moments — but even more with literary and pop culture references.

A pastiche of the many horror, supernatural fantasy, sci-fi, adventure, and superhero tropes that filled midcentury American life, Lovecraft Country places Black characters at the forefront of those stories and watches how they shift as a result. In Lovecraft Country, it’s the cosmic terror that’s banal; racism in daily life is the true existential dread.

Even the show’s title is a reference — to H.P. Lovecraft, the man whose work is synonymous with weird fiction, the subgenre of horror fixated on cosmic dread, and which infuses nearly all modern horror. Unfortunately, Lovecraft was also horrifically racist, and the new TV series is an attempt to acknowledge the debt that modern horror owes to him while repudiating the racism at the center of his work. The series is closely based on Matt Ruff’s 2016 horror novel of the same name, which Ruff wrote in response to the wider cultural debate about how to handle Lovecraft. Both the book and the show use a vast array of pop culture references to make you constantly aware that they are aware of the tropes they’re playing with.

The series’ first episode is especially overt in this regard. The entire opening sequence is a midcentury American geek’s dream, full of aliens and heroes and a stirring voiceover (that is, itself, a reference). This technique of using radio and musical voiceovers to narrate and underscore the action is one the show uses throughout its first season — and it’s just one more element that makes Lovecraft Country so fascinating.

Below, we break down each of the main references and callouts of episode one, “Sundown.”

Jackie Robinson

The opening monologue we hear in the first sequence of “Sundown” is a quote from the 1950 biopic The Jackie Robinson Story, a rosy recounting of the first officially acknowledged Black baseball player to join the Major Leagues. “This is the story of a boy and his dream,” the narrator recounts as our hero, Atticus, a.k.a. Tic, literally dreams of fighting a war, first against enemies in the trenches, and then against giant UFOs and flying Cthulhus. “But more than that, it is the story of an American boy and dream that is truly American.”

A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs

This is the book we see Tic reading on the bus in “Sundown,” the book that’s prompted his fantastical dream sequence. Written by Edgar Rice Burroughs of Tarzan fame, A Princess of Mars is the first installment of the series of sci-fi adventure novels known as the John Carter series. They’re also known as the Barsoom series, so named for the alien land that Carter, a “Virginia gentleman” and Confederate general, encounters when he unexpectedly finds himself on Mars. In Tic’s dream, he greets a beautiful alien who descends from a UFO, a likely reference to the book’s titular princess.

The princess speaks to him in a creepy unknown language. That’s a common trope of Lovecraftian fiction, so perhaps it’s the Lovecraftian language of R’lyehian. It seems more likely, however, that it’s a fragment of a different language — one we’ll encounter later in the series, and which Tic might not even know that he knows.

Weird Tales

Weird Tales was a popular magazine that ran from 1923 to 1954, and thus fueled much of the geek culture zeitgeist for the first half of the 20th century. It published numerous works of horror by H.P. Lovecraft, as well as many other influential writers like Ray Bradbury. Perhaps more importantly, it helped give rise to the term “weird fiction,” which is still used today to describe the specific subgenre of cosmic horror infused with existential dread that Lovecraft popularized.

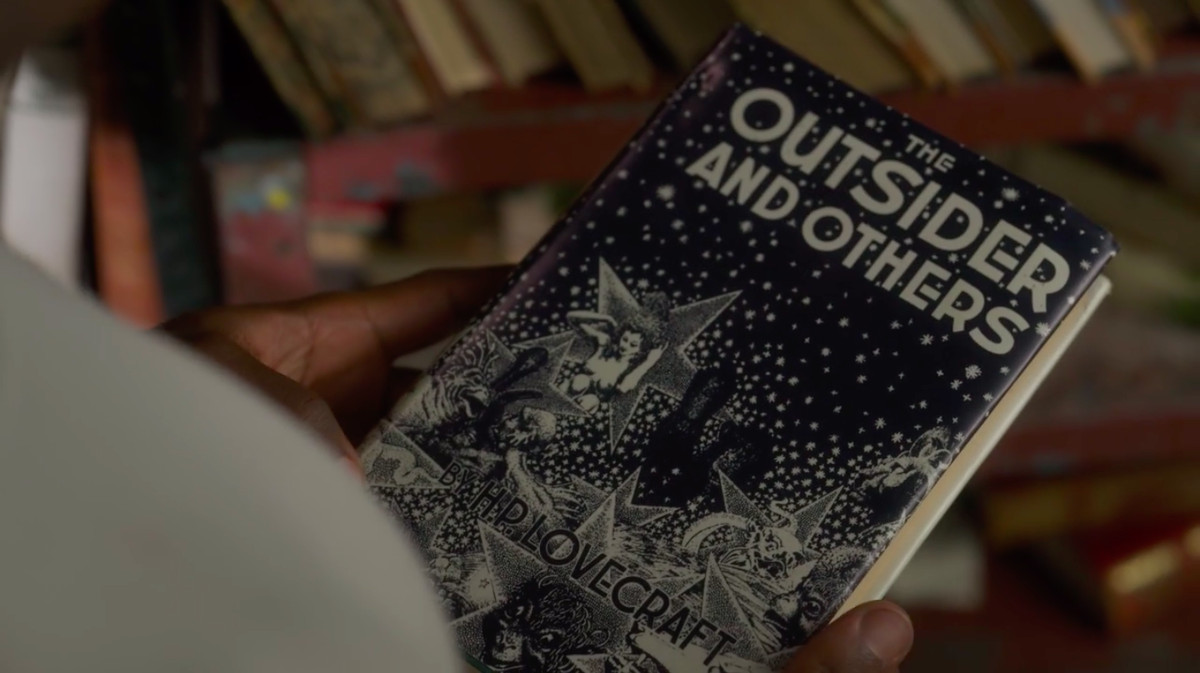

The Outsider and Others by H.P. Lovecraft

One of Lovecraft’s collections of short stories, The Outsider and Others, is an apt choice for the first textual reference to Lovecraft on the show. The book was very influential — it contains most of Lovecraft’s most famous short stories, including the heavy hitters like “The Horror at Red Hook” and “The Call of Cthulhu.” But many of these stories are home to Lovecraft’s most direct racist metaphors and allegories — what to Lovecraft were the horrors of other races, foreigners invading America, and miscegenation.

The image is blunt: To Lovecraft, Tic is both the Outsider and the Other — and Tic knows it. A few moments later, he reminds himself and his uncle George of Lovecraft’s racist beliefs when he references one of the author’s far less well-known writings: the 1912 poem “On the Creation of N*****s,” about which the less said the better. Tic’s father, Tic explains to George, made him memorize it so he’d understand exactly what he was reading.

Arkham, Massachusetts

Arkham was a fictional Massachusetts town that Lovecraft invented and then returned to again and again in his fiction — so much so that to this day, many people think it’s a real place. Arkham was also the name of the small press through which Lovecraft published many of his works; the name of the publisher is displayed prominently on the spine of the copy of The Outsider and Others that Tic is reading.

George refers to Arkham as the home of “Herbert West — Reanimator,” another reference to one of Lovecraft’s most famous stories: a 1921 tale about a scientist who tries to reanimate the dead with less than optimal results. The story was made into a cult hit 1985 horror film, Reanimator.

Arkham is perhaps best known outside of Lovecraft as the name of Gotham’s asylum in DC’s Batverse — but that, too, is a reference to Lovecraft, and especially the ongoing theme of madness that runs through the author’s works.

The “guide book” a.k.a. the Green Book

George publishes a fictional version of “the Green Book.” The Green Book was a real series of pamphlets that offered guidance to Black Americans living under Jim Crow regarding which American towns were safe for them to stay in while traveling. (The pamphlets became much more widely known after the 2018 debut of the frequently criticized film Green Book, which went on to clinch a frustrating Best Picture win at the 2019 Oscars.) The knowledge shared within the Green Book was especially important for Black travelers to have in the North, where local attitudes were often just as fiercely racist as attitudes in the South, but weren’t advertised as overtly.

Sundown towns

One of the most pernicious ways racism manifested in the North during this period was through sundown towns, sometimes called sunset towns, which proliferated throughout northern states. They were places where Black people were unofficially forbidden to be after dark. This terrifying concept forms the basis for one of Lovecraft Country’s scariest scenes, both in the book and on the TV series, and which serves as a set piece of “Sundown” — when Atticus and friends encounter a racist cop who’s policing a sundown town.

James Baldwin debates William F. Buckley

[embedded content]

In 1965, eminent Black writer and scholar James Baldwin was invited to Cambridge University to debate the question, “Is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro?” with prominent conservative William F. Buckley. Baldwin emphatically won the debate, in a speech that would later be titled “The American Dream and the American Negro.”

In “Sundown,” an audio excerpt from Baldwin’s speech is overlaid with a montage of the group’s road trip, as they encounter slices of Americana, often overshadowed by implied and unofficial social segregation under Jim Crow.

Elder Gods and Shoggoths

When our heroes first encounter the otherworldly monsters in the woods, George identifies them as “shoggoths.” This is a reference to one of Lovecraft’s hierarchies of monsters — groups of creatures from other dimensions that he classed into oddly named hierarchies like Shoggoths and Yog-Sothoth. At the top of the monster chain sits Cthulhu, his most famous creation — basically a giant winged tentacle monster. Shoggoths, however, are more slug-like, with fewer tentacles and many eyes.

It seems unlikely that the fast, agile creatures our heroes encounter are shoggoths, but they may very well be Elder Gods, a typical Lovecraftian term for the ancient creatures who loom out there in the cosmic void.

“The children of the night … what music they make.”

As Tic notes after George recites it, “The children of the night … what music they make” is one of the most famous quotes from Bram Stoker’s 1897 vampire novel Dracula. The vampires inspire our crew to use lights to drive away the creatures that attack them in the woods, until sunlight returns them to (relative) safety.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Posts from the same category:

- None Found