Table of Contents

The Supreme Court’s Republican majority, in a case that is literally titled Republican National Committee v. Democratic National Committee, handed down a decision that will effectively disenfranchise tens of thousands of Wisconsin voters. It did so at the urging of the GOP.

The case arises out of Wisconsin’s decision to hold its spring election during the coronavirus pandemic, even as nearly a dozen other states have chosen to postpone similar elections in order to protect the safety of voters. Democrats hoped to defend a lower court order that allowed absentee ballots to be counted so long as they arrived at the designated polling place by April 13, an extension granted by a judge to account for the brewing coronavirus-sparked chaos on Election Day, April 7. Republicans successfully asked the Court to require these ballots to be postmarked by April 7.

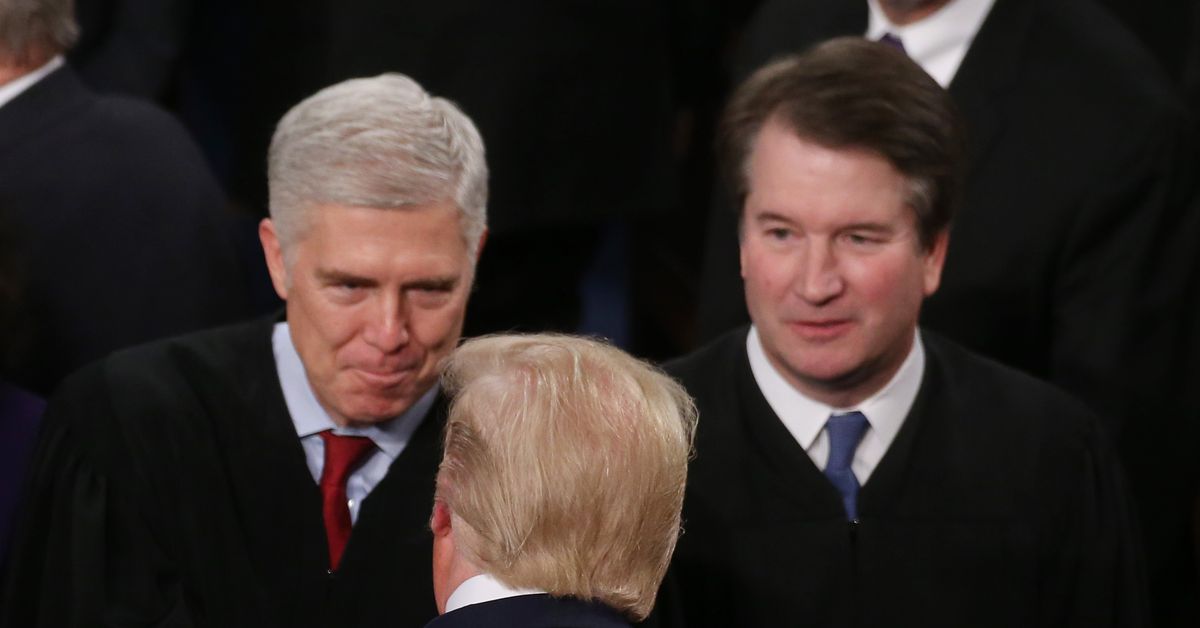

All five of the Court’s Republicans voted for the Republican Party’s position. All four of the Court’s Democrats voted for the Democratic Party’s position.

The decision carries grave repercussions for the state of Wisconsin — and democracy more broadly. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg notes in her dissent, “the presidential primaries, a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, three seats on the Wisconsin Court of Appeals, over 100 other judgeships, over 500 school board seats, and several thousand other positions” are at stake in the Wisconsin election, which will be held tomorrow. Of all these seats, the state Supreme Court race, between incumbent conservative Justice Daniel Kelly and challenger Judge Jill Karofsky, is the most hotly contested.

The April 7 election is shaping up to be a trainwreck. Most poll workers have refused to work the election, out of fear of catching the coronavirus, which forced Gov. Tony Evers (D) to call up the National Guard in order to keep polls open. But even this measure appears woefully inadequate. In Milwaukee, election officials announced that the state only has enough election workers to open five poll locations — when the city would normally have 180 polling places.

Meanwhile, the state has received a crush of absentee ballot requests — about 1.2 million, when it typically receives less than 250,000 in a spring election. That’s left state officials scrambling to send ballots to voters in time for Tuesday’s election. And on top of all of these complications, a state law required all ballots to be received by election officials by 8 pm on April 7, or else those ballots would not be counted.

Tens of thousands of voters are not expected to even receive their ballots until after Election Day, effectively disenfranchising them through no fault of their own.

In response to this brewing catastrophe, Judge William Conley, an Obama appointee to a federal court in Wisconsin, ordered the deadline for receiving ballots to be extended to 4 pm on April 13. In response to this order, the Republican Party asked the Supreme Court to modify Conley’s decision to require all ballots to be postmarked by April 7 or they will not be counted.

The Supreme Court’s Republican majority granted the GOP this very specific request.

Again, many voters are not expected to receive their ballots until after this April 7 deadline. As Justice Ginsburg notes, “as of Sunday morning, 12,000 ballots reportedly had not yet been mailed out,” so the number of voters disenfranchised by the Court’s order in Republican is likely to be vast. The Court’s decision in Republican, moreover, is the culmination of a weeks-long effort by Republicans to thwart various efforts by Democrats to accommodate voters who might be disenfranchised by coronavirus.

The majority relied upon one of the most destructive voting rights decisions of the modern era

The majority opinion, which is unsigned, relies heavily on the Court’s previous decision in Purcell v. Gonzalez (2006). Purcell is by no means a famous decision. It received far fewer headlines that the Court’s decisions striking down much of the Voting Rights Act or permitting partisan gerrymandering. But it’s proved to be one of the greatest thorns in the side of voting rights advocates. And the Court’s decision in Republican cements Purcell’s status as one of the greatest obstacles facing a voting right litigator.

Briefly, Purcell held that courts should be reluctant to hand down orders impacting a state’s election procedures as Election Day draws nigh. “Court orders affecting elections,” the Court warned in Purcell, “can themselves result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls. As an election draws closer, that risk will increase.”

There is some wisdom to this vague guideline. Voters may, indeed, be quite confused if a wave of court orders are handed down close to an election. For example, if the Supreme Court of the United States were to declare, well after sunset on the eve of an election, that voters must mail their ballots by April 7 or be disenfranchised, such an order is likely to confuse some voters and lead to them being unable to vote.

In any event, there are good reasons why Purcell’s warning about courts deciding voting rights cases too close to an election should not be read as an inexorable command. For one thing, the consequences of a new voting law may not become apparent until that law is actually operating close to an Election Day. Voting rights advocates may not learn that voters are struggling to obtain absentee ballots, for example, until an election is close and many voters are complaining that they haven’t received ballots. If courts cannot intervene under these circumstances, many impediments to the right to vote will go unaddressed.

Similarly, as the Democratic Party unsuccessfully argued in its brief in the Republican case, court orders are not the only thing that can “result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls.” In Republican, voter confusion and an incentive to remain away from the polls arose from “the COVID-19 pandemic and the ‘voter confusion and electoral chaos’ it is causing.”

Until recently, the Democratic brief explained, “Wisconsin voters reasonably expected they would be able either to vote safely in person on election day or through a reliable, well-functioning absentee ballot system.” Those voters learned very close to the election that this reasonable expectation was wrong. And Judge Conley’s order was an attempt to alleviate the disruption caused by the pandemic.

Nevertheless, Republican treats Purcell’s warning about last-minute election orders as something very close to mandatory. “By changing the election rules so close to the election date,” the Court’s Republican majority claims, “the District Court contravened this Court’s precedents and erred by ordering such relief.”

“This Court,” the majority opinion added, “has repeatedly emphasized that lower federal courts should ordinarily not alter the election rules on the eve of an election.”

This conversion of Purcell from guideline to something close to a mandatory decree is likely to have sweeping consequences for future elections. It means that, if voting rights advocates discover in the final days before an election that a new state law is disenfranchising African American voters — or a pandemic keeps away most voters — federal courts most likely may not intervene. It means that many problems that are unlikely to be discovered until Election Day itself will go unaddressed.

Republicans have fought tooth and nail to make it hard to vote in Tuesday’s election

The Supreme Court’s decision in Republican is the capstone of a weeks-long effort by the Republican Party to make it difficult for voters to actually cast a ballot in Wisconsin. Last week, Gov. Evers called the state legislature into session and asked it to delay the election. But the Republican-controlled legislature ended that session just seconds after it was convened. After Evers acted on his own authority to delay the election, the state’s Supreme Court voted along partisan lines to rescind Evers’s order. Republicans also rejected Evers’s proposal to automatically mail ballots to every voter in the state.

The background is that Republicans hope to hold onto a seat on the state Supreme Court, which is up for grabs in Tuesday’s election. As law professor and election law expert Rick Hasen recently noted, “only 38% of voters who had requested an absentee ballot in heavily Democratic Milwaukee County had returned one, compared with over 56% of absentee voters in nearby Republican-leaning Waukesha County.” So there’s at least some evidence that, if additional voters are unable to return their ballots, Republicans will be overrepresented in the ballots that are counted.

It’s also worth noting that, if Wisconsin had free and fair elections to choose its state lawmakers, Evers would most likely have been able to work with a Democratic legislature to ensure that Tuesday’s election would be conducted fairly. In 2018, 54 percent of voters chose a Democratic candidate for the state Assembly. But Republicans have so completely gerrymandered the state that they prevailed in 63 of the state’s 99 Assembly races.

There is far more at stake in Wisconsin, moreover, than one state Supreme Court seat. Wisconsin could be the pivotal swing state that decides the 2020 presidential election. The question of whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden occupies the White House next year could easily be determined by which man receives Wisconsin’s electoral votes.

And the Court’s decision in Republican suggests that the Supreme Court will give the GOP broad leeway in how US elections should be conducted.

Posts from the same category:

- None Found