Table of Contents

What California went through last week was absolutely bonkers.

To avoid sparking wildfires during particularly dry, windy conditions, Pacific Gas & Electric — PG&E, the state’s largest utility provider — shut off electrical service to some 738,000 people, a deliberate blackout unprecedented in the history of the nation’s electrical system.

There’s probably no pleasant way to do something like that, but still, PG&E did it very poorly. Residents had little warning, in some cases less than 24 hours. Nursing homes, emergency rooms, police stations, and fire stations scrambled for backup generators. People with powered medical equipment or refrigerated drugs scrambled to find care at understaffed community centers, and 1,370 public schools lost power; 400 of them sent 135,000 students home to parents scrambling to cover jobs they had no way to get to.

Highways, roads, and intersections went dark without notice and caused traffic accidents. Food rotted in freezers, houses, and grocery stores. Government phone lines were overwhelmed. On top of everything else, PG&E’s website went down.

As Elizaveta Malashenko of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) put it to the New York Times: “It’s pretty much safe in saying, this did not go well.”

Until more data comes in, it won’t be possible to know how much the blackouts cost the state, but Stanford’s Michael Wara, an expert on electricity policy in California, estimates the total will come in somewhere between $1.8 and $2.6 billion.

If the rest of the country was vaguely aware that there were blackouts in California, what many don’t yet fully understand is how ugly it was and how pissed off people are. And above all, they don’t understand one of the most bonkers features of the whole situation: Everyone agrees it is going to happen again.

Indeed, blackouts like last week’s are likely to be a feature of life in the state for years to come. Region 9 of FEMA, which covers California, called them the “new normal.”

Some areas of California could see 15 or more blackouts a year, lasting two to five days. And though their impact can be better mitigated and regulators and legislators are thundering at utilities to deal with them better, there is little prospect of eliminating them.

Large-scale, deliberate blackouts are a thing in California now

It’s not just PG&E. All of California’s utilities, in consultation with the CPUC, have decided that shutting power off to large swathes of customers is safer, all things considered, than leaving it on during high wildfire risk conditions. All of them have plans to address the growing danger of wildfires, and all of those plans involve recurring Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPSs).

What’s worse, as blackouts increase, rates will increase alongside them, as utilities invest in long-delayed maintenance and safety measures. Soon the state’s electricity customers will be paying more for worse service.

How did California end up in this semi-apocalyptic situation? It is a confluence of several trends and pressures, some natural, some of human origin, all of which have been building steadily in the background. Plenty of people in both the public and private sectors had to look the other way for a long time to allow this to happen.

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he answers. “Gradually, then suddenly.” Here’s where California has found itself, gradually, then suddenly: heat rising in perpetuity from climate change, decades of poor land and forestry management coming due, hundreds of thousands of miles of aging power lines strung through dry forests, billions of dollars in liability (and billions more to come) being allocated through the bankruptcy proceedings of a corrupt, mismanaged, politically connected utility, and a future that promises the nation’s most expensive, least reliable electricity service.

It’s not pretty. In my next post, I’ll get into some of the ways California can address this problem, including what I think is the only true long-term solution. (No spoilers!)

In this post, though, I’m just going to walk through some of the main factors that led the Golden State to this impasse and explain why, as with so many things related to climate change, there is no going back to normal.

Speaking of climate change, let’s start there, because whatever else California’s tangled story is — and it is many things — it is a parable about the challenges of adapting to a changing climate.

California’s forests have become tinderboxes

Fires are growing more common and more severe in California. In the last 10 years, the state has had five of its 10 largest wildfires ever, and seven of its 10 most destructive. (These grim facts and more can be found in a report on wildfires and California’s future commissioned by Newsom, published in April.)

Two basic forces are to blame.

The first is climate change. The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer covered a paper out in July that finds, “since 1972, California’s annual burned area has increased more than fivefold, a trend clearly attributable to the warming climate.” The increase mainly shows up in hotter summers and more summer fires, though the climate fingerprint is getting clearer in the rise of fall fires as well.

In California, climate change is projected to cause more frequent and intense droughts, followed by intense periods of rain, which prompt the growth of thick underbrush, which then dries out in the subsequent droughts and becomes kindling. “Each degree of warming causes way more fire than the previous degree of warming did,” climate scientist Park Williams told Meyer.

And the state is not alone: Research shows climate change is already increasing the number of weather-related outages across the country.

The second factor making the state more fire-prone is poor forest management. Earlier this year, journalist Mark Arax published an extraordinary feature story on the Paradise fire, California’s most destructive fire ever (before which PG&E considered, but decided against, a PSPS). In it, he tells the tale of how, in the 1990s, the state’s timber industry came to be dominated by rampant clear-cutting. Varied, diverse forests, with patches of scrub and trees alternating, served as natural fire breaks. Wildfires came to them periodically, as is natural and necessary for regeneration, but they did not spiral out of control.

After a clear cut, forests are replanted as monocrops. There are no natural breaks, no variation, which makes them extraordinarily vulnerable to rapidly spreading fire.

And in the early 2000s, the forestry management practiced by state park rangers — prescribed burns, clearing brush, remediating clearcuts — fell out of favor relative to an increasingly large, paramilitary fire brigade. “As rangers joined up with the ranks of better-paid firefighters,” Arax writes, “their numbers dwindled to maybe 250, even as the number of firefighters inside the [Department of Forestry and Fire Protection] jumped to 7,000.” Firefighters put out fires. But consistent fire suppression only increases the amount of dry, flammable material.

As this LA Times story reveals, California’s clearcutting and forest mismanagement continue to this day.

More and more people are building (and rebuilding) in fire-prone areas

California has a housing crisis, born largely of the fact that wealthier urban residents refuse to allow more housing to be built in urban areas, near jobs. Consequently, as more residents stream into the state, the price of existing urban housing stock rises and development sprawls outward. More and more of that development is being pushed into the “wildland-urban interface” (WUI), where wildfires are more frequent and more difficult to fight.

Again, California is not alone. A 2018 study in PNAS found that, between 1990 and 2010, the WUI was “the fastest-growing land use type in the conterminous United States.” This is happening in lots of states.

But it’s particularly concentrated in California, where a million houses were built in the WUI during those same years. In Mother Jones, Jeffrey Ball has a feature story on the state’s terrible land-use policies, which encourage sprawl, and specifically building (and rebuilding) in fire-prone areas, in a dozen different ways, including subsidized insurance. (See also this piece by James Temple.)

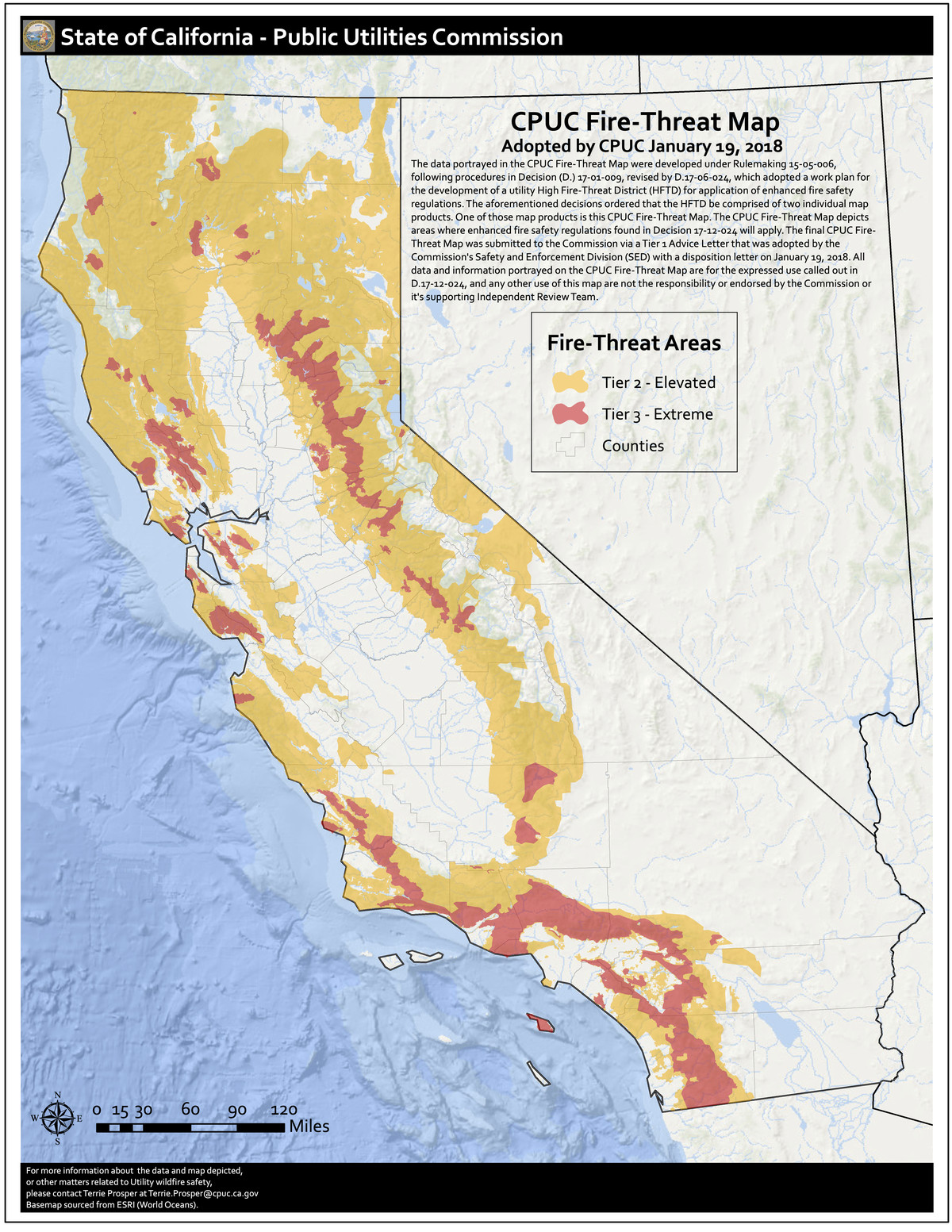

As a result, fully half of California citizens now live in areas of high wildfire threat.

Add all this together — increasing heat from global warming; several years of unusually high winds and low humidity; poor logging practices with fewer preventative burns; more people living on forested ridges and hills in remote, fire-prone areas — and the result was disaster.

The year 2017 was the most intense and deadly wildfire season in the state’s history. Alongside 47 dead were 1.4 million acres and 9,470 homes and businesses burned. The insured losses added up to a staggering $13.2 billion.

Then came 2018. July 2018 was the hottest month ever recorded in California; the state was five degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the historical average. In the end, more than 8,000 fires left 104 people dead, 1.9 million acres burned, and more than 19,000 homes and businesses destroyed. The insured losses came in at $12.4 billion.

And here’s a fateful quirk: California law makes power utilities legally liable for the damages from wildfires they start, under a doctrine known as “inverse condemnation.” Heading into the 2019 wildfire season, California lawmakers hastily passed a law providing utilities some relief from that provision, but it was too late for PG&E, which serves 16 million customers in central and Northern California. Its power lines had, it turned out, started many of the worst fires. In January, groaning under more than $30 billion in debt for those damages, it declared bankruptcy.

So, let’s talk about PG&E.

PG&E is a steaming pile of terrible management and debt now at the mercy of a bankruptcy judge

PG&E is, according to consensus opinion across California, just The Worst.

The power shut-offs by PG&E are not a story of climate change. It’s a story of greed and mismanagement. Of recklessness and putting profits before people. It’s outrageous and unacceptable. pic.twitter.com/8ecLSts9Za

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) October 11, 2019

In addition to its statewide network of natural gas pipelines, the utility maintains some 26,000 miles of underground electric lines and almost 100,000 miles of overhead lines, many of which travel miles through heavily wooded territory. (Overall, the state has more than 250,000 miles of overhead lines.)

If power lines throw off sparks or “sag” from excess voltage and touch plants or structures, or if plants and trees grow too close to lines and are blown into them, the sparks can generate intense wildfires. Between 2014 and 2017, there were more than 2,000 “ignition events” caused by power lines in California, which averages out to 1.5 fires a day.

A state investigation concluded that it was an aging PG&E transmission tower that caused November 2018’s Camp Fire, the deadliest wildfire in the state’s history, which killed 85 people and wiped out the town of Paradise.

Court records subsequently revealed that PG&E equipment had caused 435 fires in 2015 and 362 in 2016. It 2017, its lines caused the North Bay Fires, which burned 200,000 acres and were the largest wildfire disaster in state history until the Camp Fire, which, again, PG&E also caused.

It must be said that PG&E faces a physically more difficult task than Southern California utilities. It manages giant swathes of often sparsely populated territory, where it must maintain lines that run through hundreds of miles of hilly and sometimes mountainous forest. Given that the state is becoming a giant tinderbox and houses are invading wilderness everywhere, it’s just impossible to string power lines to everyone without starting some fires.

But it must also be said that PG&E has long been wildly corrupt, incompetent, and cozy with regulators. It lavishly funds state politicians; state records show that it has donated to 8 out of 10 California legislators. It spent $208,000 just electing Newsom.

Over the years, coziness with the people meant to be overseeing it has led to a lax safety culture. As Katherine Blunt and Russell Gold reported for the Wall Street Journal, PG&E has known for years about the increasing fire risks around its decrepit, outdated infrastructure. And despite a lot of talk, and a lot of money taken from ratepayers for the purpose, it has systematically neglected basic inspections and maintenance and has done very little to improve its ability to predict, avoid, or manage wildfires. Instead, it took all that money (around $4.5 billion) and paid handsome dividends to shareholders.

Arax describes the legal cases being filed by the attorneys representing a class of more than 1,000 people who lost property in the 2017 and 2018 fires:

In their filings, each attorney traced the historic blazes to a culture of mismanagement, corruption, and cover-up that had taken hold inside PG&E decades before. A pattern of venality, they argued, began in the company’s early years and became more recalcitrant in the 1980s and 1990s, when PG&E, with the connivance of the California Public Utilities Commission, its watchdog, made a decision to place profits and bonuses to top executives — and dividends to shareholders — over safety.

In court this year, federal Judge William Alsup was confounded. “The drought did not start the [Camp Fire]. Global warming did not start the fire. PG&E started it. What do we do? Does the judge just turn a blind eye and say, ‘PG&E, continue your business as usual. Kill more people by starting more fires’?”

That case led to a guilty verdict on five counts of willfully breaking federal safety laws and one count of obstruction, bringing a $3 million fine and five years of probation. Alsup also ordered the company to do a paragraph-by-paragraph response to the Wall Street Journal story and forced PG&E executives to take a walking tour of Paradise to witness what they had wrought. (They did but in secret.)

Bankruptcy could shield PG&E from further lawsuits and force all litigants into negotiations. With $30 billion in debt (compared to annual operating revenue of less than $13 billion a year for its electricity business) and stock that analysts say may well hit zero, PG&E’s ultimate fate is in the hands of a bankruptcy judge, though the CPUC and the legislature will want to have their say.

In the meantime, the utility is scrambling to catch up on maintenance and fire safety in the face of a huge backlog. And it is being hyper-cautious. More fires this year could mean yet more liability. It has every reason to prefer a PSPS — the damages of which it is not liable for — to even a modest risk of fire, which might help explain why its outages last week were so blunt and sweeping. As the LA Times reported, the utility “shut down nearly 100 transmission lines” that “stretched across 2,500 miles and linked to an additional 25,000 miles of distribution lines that also lost power — more than enough to wrap once around Earth.”

Customers and ratepayer advocates complain that the company is overreacting out of its own financial interests. State senators are getting involved.

It’s very possible PG&E is being extra-conservative with power shutdowns because a fire during the firm’s bankruptcy case would be harder for them to deal with than a fire outside of bankruptcy. This thread explains why (1/

— Jared Ellias (@jared_ellias) October 10, 2019

Power is now back on for the customers who lost it in the initial PSPS, but there will be more. The age, condition, and vulnerability of the California grid have been exposed.

California’s grid is deeply and fundamentally vulnerable

In August 2018, the Newsom signed SB 901, a bill that addresses a number of utility/wildfire issues. Among other things, it requires all state utilities to come up with comprehensive Wildfire Mitigation Plans. Utilities have now submitted those plans and the CPUC has approved them.

PG&E’s plan is revealing. It promises to attack the backlog of maintenance and do other kinds of grid hardening (more on that in the next post), but it is also frank about the fact that such work will take up to a decade, and in the meantime, there will be more PSPSs. Other utilities say largely the same thing.

Utilities can learn to forecast better, target their blackouts more precisely, offer customers more warning, and make better plans for basic community needs during blackouts, but it probably can’t eliminate them. Given that wildfire risks are only growing, it’s entirely possible that sporadic blackouts will simply be a fact of life in what was, until recently, considered one of the world’s most advanced economies. And that will happen alongside rising rates.

Very little is known about the economic costs or health and safety risks of these planned blackouts. (Catherine Wolfram of the Energy Institute at Haas discusses some of the difficulties in measuring damages here.) But their costs will be enormous, in medical crises, lost workdays, and simple stress and uncertainty.

As we’ve already seen, PG&E was criticized for not cutting off power before the Camp Fire, but it was also criticized for cutting it off last week. As terrible as PG&E is, there is no winning that game. Californians don’t want to change where they live, or their zoning codes, or their building codes, or how much they pay for power. Nonetheless, they are going to be righteously pissed off when their electricity starts getting regularly shut off, and they’re going to want someone to blame. It is going to be an absolute political shit show for PG&E — or whoever operates its assets once this is all over — for the foreseeable future.

So what can be done about it? Must California simply accept this state of affairs?

To some extent, the unpleasant answer is yes. There are certainly better and worse courses of action the state could take, better and worse outcomes, but there is no going back to “normal.” It can adapt to the riskier, more volatile environment that is coming, maybe even learn to thrive in it, but doing so will involve enormous changes.

In my next post, I will look at some of those changes. Some have to with improving the existing grid and fire-safety procedures; some have to do with changing where and how residents build; some have to do with reforming (or breaking up) PG&E; but the main change, the inevitable and necessary change, is a change in the structure of the electricity system itself, the way it is designed and managed, to reduce the dependence of far-flung Californians on what have proven fairly hapless centralized authorities.

Posts from the same category:

- None Found