Table of Contents

Earlier this month, Pennsylvania’s governor announced his state was moving to join the Northeast’s carbon market, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. In 2018, we explained how the states that are already part of RGGI are receiving substantial dividends from the program while also reducing emissions. Read it here:

When climate hawks fantasize about climate policy, they tend to imagine a sweeping, economy-wide carbon tax, set at a high and rising rate. But as a political strategy, this hasn’t much worked; political restraints have meant that no such tax has emerged in the real world.

But there is another political strategy, far more popular among actual policymakers. It goes something like this: The wise course is to start with a relatively low carbon price, targeted at sectors amenable to carbon reductions, and spend the revenue from it on things that clearly benefit the public. Set up that system, show that it can work, and then ratchet up its ambition until it is adequate to the task.

This more incremental strategy is less sexy, but unlike the perpetual craving for revolution, it has gotten the ball rolling. According to the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, some 42 countries and 25 subnational jurisdictions now price carbon.

None of these carbon-pricing systems is reducing enough carbon fast enough. We still don’t know if it’s politically possible to get a price high enough to drive radical carbon reductions.

What we do know, what has been amply demonstrated, is that it’s possible to set up a transparent, well-run carbon-pricing system that economically benefits the jurisdictions where it’s implemented and is politically resilient.

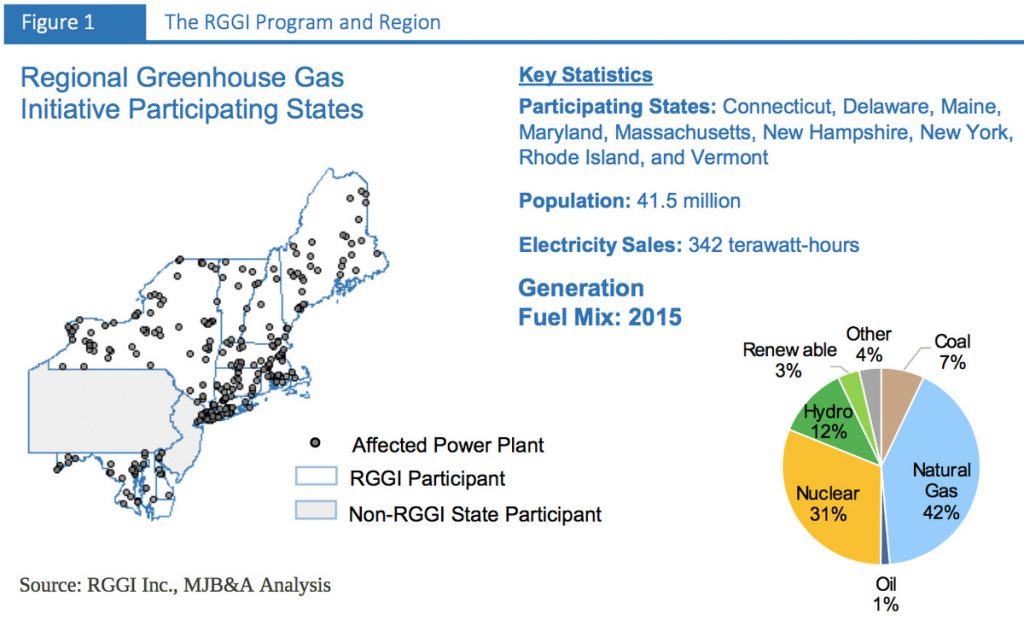

Exhibit A is right here in the United States: the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a cap-and-trade system covering the power sector in 10 Northeastern states, including Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. (New Jersey recently rejoined after Democrat Phil Murphy was elected governor; Virginia may also join in the wake of the election of Democrat Ralph Northam.)

I wrote a longer post about RGGI here if you want to dig into the details; for now, let’s just look at the benefits accruing to the states involved. Perhaps if more jurisdictions are convinced that carbon pricing is a net benefit, some of the political resistance to higher carbon pricing can be eroded.

The RGGI cap is not driving most of the electricity-sector emission reductions

Since RGGI started in 2009, the Analysis Group has periodically assessed its economic impact on participating states. Its latest report, out last week, is of particular interest, as it covers the three-year compliance period from 2015 to 2017, a period that saw quite a bit of change.

The economics of renewable energy changed, pollution control regulations changed, and some of the rules that govern regional energy markets changed, but most significantly, in December 2017, RGGI states completed their second mandatory Program Review, which resulted in a number of revisions to the program. Most notably, the regional carbon cap between 2020 and 2030 was reduced by 30 percent.

That last part is important because the dirty secret of RGGI is that, so far, the carbon cap on the electricity sector (the dotted line) has been far above the sector’s actual emissions (the solid line):

The way-too-high cap was the result of two things: one, the overweening caution of policymakers pioneering one of the first carbon-trading systems, and two, the fact that electricity-sector emissions have fallen much faster than expected, all over the US.

It is only with the 2014 revisions to RGGI that the cap even got close to actual emissions, and only with the 2017 revisions that the cap threatens to actually start pushing them down faster than their “natural” rate in the long term.

For now, emissions are still falling faster than the cap is declining. The cap is not driving that, for the most part. At least not yet. But the program is still working, thanks to three clever features built in from the beginning.

RGGI is paying economic dividends to participating states

First, the pollution permits distributed under the cap are not given out for free; they are auctioned. That guarantees that each state receives a stream of revenue.

Second, no matter how little pressure the cap puts on emissions, the price of permits never falls below a set reserve price (just over $2 in 2017), so there’s always at least some revenue.

And third, much of the revenue goes to “consumer-benefit programs,” including energy-efficiency programs and direct bill assistance. By agreement, 25 percent of the revenue is to go to such programs, but in practice, the total has been much larger.

“As in the prior years,” Analysis Group writes, “during the 2015-2017 period [RGGI] states received and spent the roughly $1.0 billion in auction proceeds primarily on energy efficiency measures, community-based renewable energy projects, customer bill assistance, other GHG-emission reduction measures, and on research, education and job training programs.”

The best way to think of RGGI, then, is as a relatively low carbon tax that transfers money from the owners of fossil fuel power plants to consumer-benefit programs.

According to Analysis Group, it’s a pretty good deal for the states involved — the benefits of the investments outweigh the costs to consumers in higher electricity prices. In the 2015 to 2017 period, “the RGGI program led to $1.4 billion (net present value) of net positive economic activity in the nine-state region.” Every participating state’s economy and electricity consumers benefited.

Here’s how the economic impacts break down by energy market:

Spending money on efficiency and renewable energy programs is also good for jobs. Over the 2015 to 2017 period, taking into account gains and losses, Analysis Group estimates that RGGI led to “over 14,500 new job-years, cumulative over the study period, with each of the nine states experiencing net job-year additions.”

Most RGGI states are not big fossil fuel producers, but most of the region’s power comes from fossil fuels, so fossil fuel imports are an enormous expense. Over the study period, Analysis Group estimates that RGGI states reduced spending on imported fossil fuels by $1.37 billion.

For RGGI states, carbon policy has not been a sacrifice.

What can be learned from RGGI

As Analysis Group emphasizes, RGGI was not intended or designed to be an economic development policy. Ultimately, it should be judged by its success in gradually ratcheting down emissions from the power sector.

Power sector emissions are down and the program is operating smoothly. That RGGI accomplished both while imposing no economic sacrifice (the opposite, actually) has to do with the fact that emissions were already on their way down — and that energy-efficiency investments are smart because the savings compound over time. Diverting money from fossil fuels to energy efficiency would produce a net economic benefit for any state, using almost any policy mechanism.

But right now, RGGI amounts to a small carbon price on a small portion of the region’s emissions. It remains an open question how a program like RGGI would fare if it expanded into sectors less amenable to carbon reductions, like transportation or industry (sectors it is becoming increasingly urgent to address).

Really interesting concept for an RGGI type program for transportation. After the success of RGGI on energy production, some think its time to give it a shot in the transportation sector and see if it can solve two of MA’s biggest transpo problems… https://t.co/1vCHblf3gS

— William Rurode (@werurode21) April 24, 2018

Theoretically, a rising price on carbon could eventually make gasoline vehicles so expensive that consumers are forced en masse to EVs. But they might not be so sanguine about that as they are about small bumps in their electricity bills. When it comes to more stubborn sectors, progress is unlikely to unfold in the benign, orderly way that RGGI has proceeded so far.

Basically, we don’t know what it looks like for a price on carbon to get high enough to emerge as a primary driver of rapid emission reductions. What we do know, thanks to RGGI and other systems, is that carbon-pricing systems can get established, nudge emission reductions along, and build some political capital.

For the incrementalist political strategy to pay off, though, RGGI has to spend some of that capital and keep ratcheting up. Its true test will only come when its reach gets broader and its prices get higher.

Posts from the same category:

- None Found